Modernizing the Grid: Lines and Poles

When people speak of the “grid,” they often do so with hand-waving generality. As if the grid is a single entity across a single region. This is far from the truth, with grid infrastructure varying greatly depending on local and regional location.

For instance, the Texas grid is completely closed off from the rest of the US, which caused issues during a major winter storm earlier this year. They could not import any power due to their isolation.

What we’re saying is: The “grid” is far more complicated than a collection of lines and poles.

In a three-blog series, we will go over several pieces of the grid: the lines and poles, generation and load, the grid operators, and finally the clean energy solutions that will change the grid as we know it.

Grid infrastructure is an often-neglected piece of climate policy. However, the modernization of the grid, and the investment necessary to do that, is key to a future powered by clean energy.

But let’s start with those all-important lines and the poles.

The American grid is actually three grids: the western interconnect, the eastern interconnect, and Texas.

Within these larger interconnects is a mosaic pattern of transmission lines, distribution lines, and feeders. Some are above ground, like the gigantic transmission lines you can see parallel to many interstate highways, and some are below ground, buried for cost savings and protection from weather events like wildfires.

One of the most intuitive ways to understand the grid is through the analogy of our road system. We will use that to cover the details and importance of the lines and poles.

Basic Structure of the Electric System

Cars on the Road

Fundamentally, the grid, and the electrons that flow through it, are like cars on various roadways.

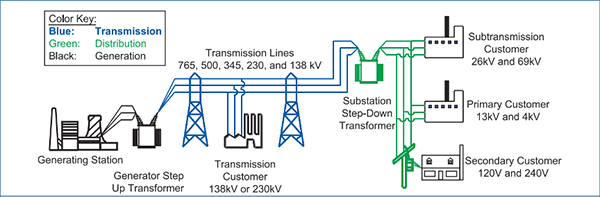

All electricity starts at a generation source. This could be a solar array, a wind farm, or a coal-fired power plant (hopefully not though), etc. Once the electrons are generated, they go through a device called a transformer, which “steps-up” the voltage.

“Stepping up” is an accurate moniker, as it means the voltage is increased. Stepping up is done to prevent losses during the movement of the electron from generation to powering your home, business, or anything else that needs electricity. Transformers are often found in substations. Substations are areas that house the transformers that step up or step-down voltages.

They can be found at multiple levels of the grid, but we will focus on distribution level and transmission level substations. For the purpose of this blog, and the roadways analogy, you can think of substations like the on or off ramps to the grid.

After being generated, and then stepped up through a transformer, the electrons (cars) can take one of these on-ramps (substations) to one of two routes: the transmission lines (think interstate) or the distribution lines (highways/local roads).

Interstates

First, we have the interstates. These are transmission lines that can carry high-voltage electricity across large distances. The high voltage allows for less electricity to be lost during the transportation. This is akin to the higher speed limits allowed on interstates.

Often transmission lines are called HVDC, high voltage direct current. This means electricity at a high voltage (100+ kilovolts (kV)) flows one way (direct current), as opposed to high-voltage alternating current (HVAC). HVDC is preferred over the longest distances and is often referred to as the “backbone” of our grid.

Once the electricity has traveled to the location where it will be used, it leaves the transmission lines through a transformer, where it is stepped down. Think of this action as taking an off ramp. The stepping down is necessary because the distribution power lines cannot handle (aka, are not rated for) the higher voltage. In the analogy, you take the exit ramp onto a smaller highway or local road, where you drive at a slower speed limit.

The aggregation of end use is often called “load.” Load will be important in later blogs as you have load centers (cities or industrial electricity users) that greatly influence how the grid is run and constructed.

Highways or Local Roads

Now, the electricity is flowing through a distribution line. Distribution happens at the local level. These are the lines and poles you see in your community.

Note that some electricity comes to the distribution lines from the transmission lines and some electricity is generated directly onto the distribution lines. Injecting directly onto the distribution lines often comes from smaller generation, like smaller solar farms, rooftop solar, or battery storage.

Keeping with the road analogy, on a two-lane highway, some cars got there by exiting the interstate (transmission), and some may have pulled onto it from a local road or even their own driveway (feeders).

Driveways

Finally, the electricity flowing through the distribution lines gets to its end use. This could be a business, an EV charging station, or your home. This is done through feeder lines, which are part of the distribution grid.

The electricity is stepped down through a transformer from a larger distribution line (highway or local road) to a smaller distribution line called a feeder, which in the analogy is your driveway. This brings the voltage to a useable rate for your home or business.

You can see these transformers out on the poles down your street or elsewhere in your community, and they usually take the form of grey cylinders on the tops of power lines.

To give perspective on voltage changes through this process, electricity is generated anywhere from 11 to 25 kV (kilovolts) then stepped up via transformer to 500 kV for transportation through an HVDC line, and then stepped down all the way back to 120 kV to use in your home.

We didn’t talk much about the poles themselves, but that’s because they are straightforward.

You either have poles in above ground or below ground wires. The decision between these is often made for safety, resiliency, or cost, or a combination of all three.

It’s important to note that the maintenance of the lines and poles is a major cost to utilities. Trimming trees and clearing bushes – often called “vegetation management” – is expensive. By some estimates, utilities spend $6-8 billion dollars a year on it. Burying lines means more upfront cost, but then you save on the back end with decreased vegetation management.

The grid is complex, and the next blog in this series will focus on the most maligned and talked about piece of the it: generation.

We’ll cover renewables, fossil fuels, and the differences between the power they produce; and discuss what it all means for the grid and how it is needs to be modernized to handle a truly clean-powered future.

The lines and poles are boring but important. Generation is where the fun starts!