Talking Climate and Health: IPCC Report Lead Author Dr. Kristie Ebi

Dr. Kristie Ebi is a professor of global health and environmental and occupational health sciences at the University of Washington. For over 20 years, she’s been researching the health risks of climate variability and change, focusing – in her own words - on “understanding sources of vulnerability, estimating current and future health risks of climate change, and designing adaptation policies and measures to reduce the risks of climate change in multi-stressor environments.”

Few have such a high level of expertise – and that’s why she was named as a lead author on not one, but two recent blockbuster climate reports: the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Global Warming of 1.5ºC and the Fourth National Climate Assessment. If that makes her sound like a science world rock star, well, that’s because she is.

>> 2030 Or Bust: 5 Key Takeaways from The IPCC Report <<

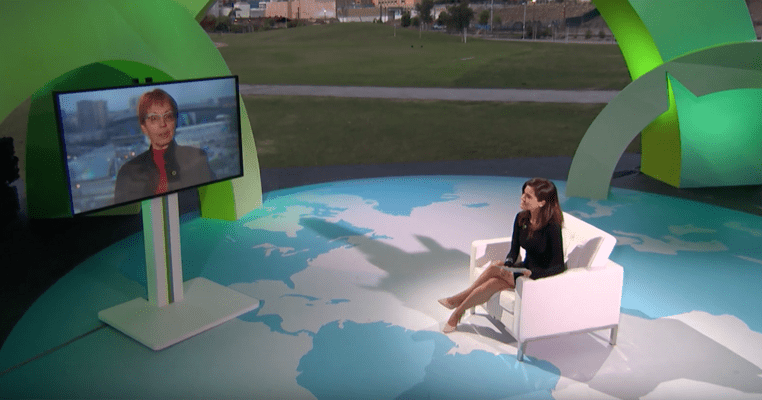

As part of our global broadcast event exploring the climate-health crisis, 24 Hours of Reality: Protect Our Planet, Protect Ourselves, we invited Dr. Ebi to join Emmy Award-winning Telemundo journalist, co-founder of Sachamama.org, and long-time Climate Reality friend Vanessa Hauc to discuss the IPCC report and National Climate Assessment, the health impacts of climate change, and why she remains optimistic that we will solve this crisis.

The interview has been condensed and edited for brevity below.

Vanessa Hauc: Professor, you were the lead author on the recent IPCC report as well as the National Climate Assessment. If you have to boil your data to a few points, what did you learn from authoring these two reports and what has changed since the previous report?

Dr. Kristi Ebi: There's a number of key messages that come out of both reports. The first is that we, of course, know that the climate is changing. But these reports detail that climate change is already affecting our health, our livelihoods, and our ecosystems in ways that are making our lives much more challenging.

We also know that each additional unit of warming will increase the level of risk. That came through very strongly in the IPCC special report. So we have very strong messages on the risks that we're facing, and how those risks are likely to evolve in a warmer world.

And further, both reports go into quite a bit of detail on the large number of options we have for being able to better manage those risks in the short term via adaptation and to reduce the risks in the long term via mitigation. And so [they] provide a really a wide range of opportunities that people can take advantage of – from the individual to the state to the national to the international scale – to ensure that we increase the resilience of our societies, so that the risks that are projected for the future don't actually turn into experienced impacts.

VH: What did you learn specifically about health?

KE: There's a wide range of risks from health, [and] I think you may have just heard about some of those from Dr. Naira from the World Health Organization. The weather affects our health directly when it's too hot or it's too cold, when there's extreme weather and climate events, when there's flooding, for example, or drought. So we know that people's health is affected very directly.

Most of the impacts on health are what we call “indirect.” These operate through changes, for example, in our atmosphere. Where there are greater levels of air pollution, there's higher levels of pollen that can affect respiratory diseases, for example.

We know that vector-borne diseases are changing their ranges, so the mosquitoes and the ticks that can carry diseases that harm human health are expanding geographically with warmer temperatures.

>> Learn more: Climate 101: Climate Change and Infectious Disease <<

That puts more people at risk of suffering from these diseases. Some people will die from these diseases. We're also seeing changes in agricultural productivity, so that crop yields are falling in many parts of the world, particularly the cereal crops that so many people rely on for most of their nutrition.

There's also new literature coming out on how rising levels of carbon dioxide are reducing the nutritional quality of rice, wheat, and other critical crops; that as carbon dioxide increases, the protein, iron, zinc, other micronutrients, and the B vitamins decline quite significantly. Which will affect hundreds of millions of people around the world.

VH: Very important findings, professor? What can we do individually and what can we lose to our public health system?

KB: Individually, it depends a bit on what kind of health outcome we're concerned about. For example, for heat waves, heat wave early warning systems save lives. The greater awareness people have of heat and the risk it presents to our health and the greater access to information means that people can take appropriate choices, so that when it is too hot outside people drink sufficient fluids. They go and find a cooling center. They make sure that they keep their core body temperature from rising too much. And we can pay attention to our neighbors. We can pay attention to our families that may be at higher risk. So we've got quite a lot that can be done.

>> Climate Change and Health: Heatwaves <<

We certainly have seen in the United States how important it is to have this kind of information. In the last year, we've had so many extreme events in the United States with floodings and in heatwaves, and far too many people have suffered and some people have died. So ensuring that we have that information and people know how to take appropriate actions [are] very important.

For other health risks such as air quality… I live on the West Coast in California, [and] we've had extensive wildfires and air quality has been worse on the West Coast at various periods in time than it has been in New Delhi or it's been in Beijing.

The options at the individual level have to really focus on having as little exposure as possible. In finding ways to for people to protect themselves, so they don't inhale too many particulates.

So there's a range of issues that individuals can take action on, but there's other actions where we really require our health systems to step in. Providing those early warning systems. Letting people know what to do when the air quality is really poor. Helping people make appropriate dietary choices as the quality of some of our food crops start to decline. Helping support people who have mental health issues following extreme events, for example.

So there's a broad basket of issues that we need our health systems to engage in. Our health systems are eager to engage. They would really like to protect population health. They would like to be able to be more effective. A main challenge has been there's almost no funding for them to do so. It's a large task for them to take on in addition to all their other responsibilities in protecting population health.

Watch the full interview:

VH: Professor, what is something that people globally don't understand and you feel they should know?

KE: It's surprising how few people understand that climate change is affecting our health. That with the release of these reports over the last few weeks, plus the report on the Lancet Countdown – and I understand you'll hear from Dr. Nick Watts later on that – that what I hear a lot is people are surprised.

They didn't realize a change in climate would affect us individually. Would affect our children. Would affect our neighbors. And so it's been very important for the media to cover these reports to the extent they have, so people can start really understanding [that] this means us. And that it means us now – and we need to start taking action now if we're to protect our health in a warmer world.

VH: Professor, how urgent in your view is the situation we are in right now?

KE: The situation is very urgent. We know from the special report on warming of 1.5 degrees that the Earth has already warmed 1 degree Celsius from pre-industrial times, and that we’ll see another half of degree of warming sometime between about 2030 to 2050. So on average in the 2040s.

And the science is very clear – that that additional half of degree of warming will present significant risks to our health, to our livelihoods, to our ecosystems.

We also know from the report that whether or not the warming of the Earth reaches 1.5, it’s up to us. It's up to the decisions that we make individually to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions. It's up to our nations as they look at how to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.

The more quickly we reduce our emissions, the faster we're going to start seeing benefits for health and the faster we’ll create new jobs through the economies that will be created as we transition from using fossil fuels to using renewable energies and to being much more efficient in how we use the energy that we already have.

VH: Professor, you have been working on climate change for more than 20 years, and I know that right now we can sound a little bit depressing, but you seem optimistic. Are you?

KE: That's a really good question. I characterize myself as a worried optimist.

When you look at the ingenuity of human beings, of what we've been able to accomplish over the course of our history, of our ability to come together in times of crises and to create new technologies to do extraordinary things, it gives you cause for optimism. We know that the actions need to be taken quite urgently for both adaptation and mitigation to really make a difference.

So I'm worried that there will be enough of a synergy, enough of a level of ambition right now to ensure that that carries forward over the next decade, so that we do have a much more resilient climate, we have a much more resilient society come 2030, and we're prepared for the changes and we take the actions we need and the projections we have of risk don't really occur because we've reduced vulnerability. We've reduced exposure, and we've made our societies much more resilient to the world that we created by emitting greenhouse gases in the first place.

VH: Thank you so much, professor, for being with us. Thank you for your time and for the wonderful job that you do.

RECEIVE UPDATES FROM CLIMATE REALITY

Our movement is at a critical turning point in the fight for common-sense solutions to the climate crisis. The good news is, the power to make meaningful progress on climate is in our hands.

But it all starts with understanding what is happening to our planet.

Sign up today to receive emails from Climate Reality and we’ll deliver the latest on climate science and innovative ways you can get involved in the climate movement right to your inbox.